Forum Theatre and Stigma in the UK & Uganda: Is it mad if it works?

What’s this all about?

I have recently returned from a trip to Butabika Hospital for the “mentally ill”, not far from Kampala in Uganda. The trip was part of a project set up by Sharing Stories – in layman’s terms, a small group of UK & Ugandan psychologists and mental health service users dedicated to improving well-being for people experiencing and working with mental health issues. The idea is that both countries are on an equal footing, neither is more important or knowledgeable than the other, but both have lots to give and learn.

Odd Arts’ partnership with Sharing Stories was a natural and obvious one – both passionate about innovative & creative approaches to mental health. Our specialisms are of course different (one applied theatre, the other clinical psychology) but complimentary. The project we have just delivered in Uganda was first delivered in Manchester to mainly UK participants, but those Ugandan members attending were keen to take the approach back to their own country and peers. The rest, as they say, is history.

The Theatre of the Stigmatised

Workshops; images of stigma

Odd Arts working with Augusto Boal, 2004

In the UK we commonly manipulate Forum Theatre, using an inauthentic (but effective) approach where actors perform a pre-scripted play, with intended intervention scenes. This allows us to tackle the contentious issues many of our participants face, in a timely and cost appropriate way which has proved to be highly effective at changing attitudes and behaviour. It gives people the chance to think critically and explore complex themes. However, a pre-scripted performance takes away the important journey, ownership and authenticity that traditional Forum Theatre allows when made by those who are themselves oppressed. Our project in Uganda went back to basics, we delivered in a format that reminds me of that which we saw in Rio 15 years ago. At that time Boal was practicing most Forum Theatre as a Politician, tackling oppression around homosexuality and mental health stigma: Some of the laws that Boal introduced were around these themes (including the banning of both Electro-Convulsive Therapy and higher prices for homosexuals in hotels). I was struck by some parallels with Uganda. Right now my understanding is that Ugandan anti-homosexuality laws have become much stricter and in some cases aggressive approaches are used within the community in the name of ‘treating’ homosexuality. Similarly with mental health, more aggressive interventions are adopted in an attempt to cure people. This latter oppression was the focus of the trip and we set about exploring mental health stigma. The group of people we worked with at Butabika Hospital were both health practitioners and mental health service users at different places of recovery. The oppression faced by this group was apparent: Lack of resources and money (both professionally and personally); ostracisation by wider society; lack of access to support.

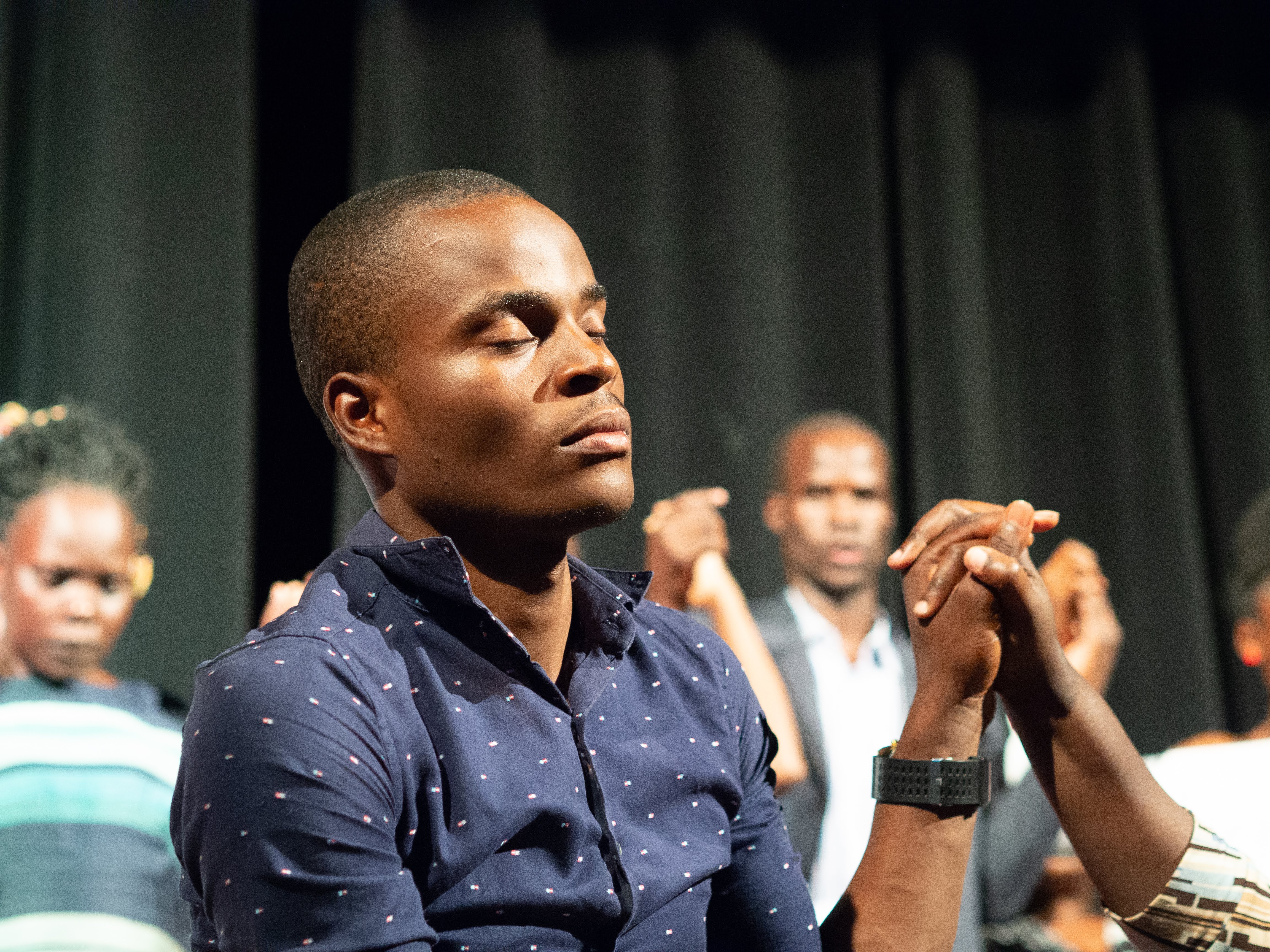

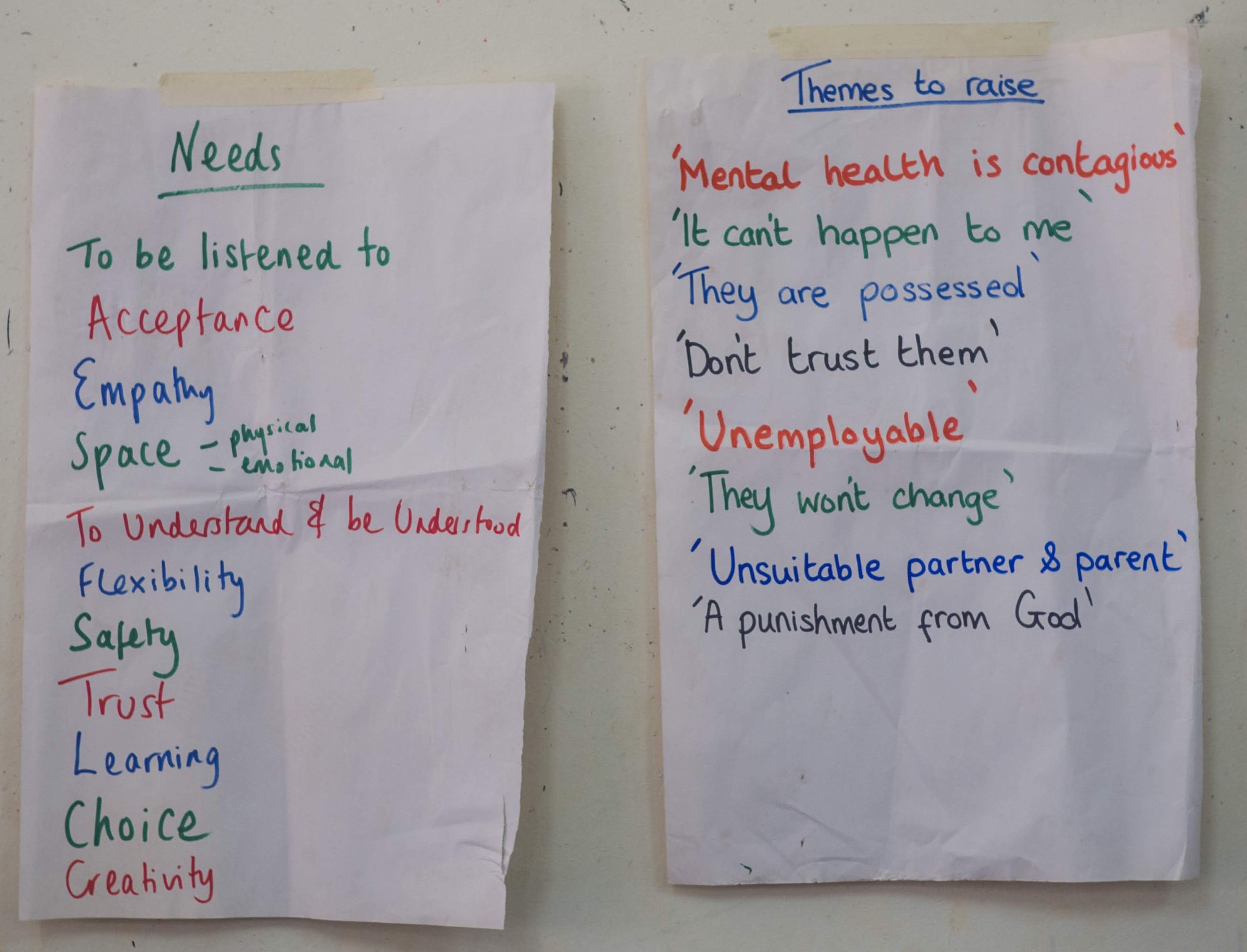

Stigma was thought to be a key cause of oppression for people experiencing mental health challenges, as well as hindering their chances of recovery and reintegration back into their community. We began the week with no idea of what would be told, created or performed, but knew every game, exercise and role play would be exploring wider themes of stigma. The performance that was created told the story of Gody (31) who struggled with depression, and Susanne (19) who had bipolar. Throughout the performance we see Suzanne’s boyfriend leave her, and her friends and college exploit and abuse her. Gody brings shame on his family and is left isolated and unemployed after his employer sacks him after finding our he had received treatment at Butabika Hospital. We rehearsed until the performance was stage ready, and shared the facilitation techniques in a Train the Trainer session to increase likelihood of lasting impact.

Stigma was thought to be a key cause of oppression for people experiencing mental health challenges, as well as hindering their chances of recovery and reintegration back into their community. We began the week with no idea of what would be told, created or performed, but knew every game, exercise and role play would be exploring wider themes of stigma. The performance that was created told the story of Gody (31) who struggled with depression, and Susanne (19) who had bipolar. Throughout the performance we see Suzanne’s boyfriend leave her, and her friends and college exploit and abuse her. Gody brings shame on his family and is left isolated and unemployed after his employer sacks him after finding our he had received treatment at Butabika Hospital. We rehearsed until the performance was stage ready, and shared the facilitation techniques in a Train the Trainer session to increase likelihood of lasting impact.

Same but different: Stigma & mental health in UK & Uganda

As a non academic and having only participated in Sharing Stories once in UK, once in Uganda, my experience is limited – however, it has highlighted some key themes that are strikingly similar:

- The widespread avoidance of discussing mental health: Whilst here in the UK, the understanding and profile of mental health is growing, there is still a real fear and avoidance of discussing mental health in the same way we do with physical health. Mental health is still seen as a danger or failure and something we like to describe as ‘other’. Likewise, in one scene created by our Ugandan participants, they depicted a family desperate to hide their son’s depression from their neighbours, removed him from sight and lied about where he was to avoid judgement.

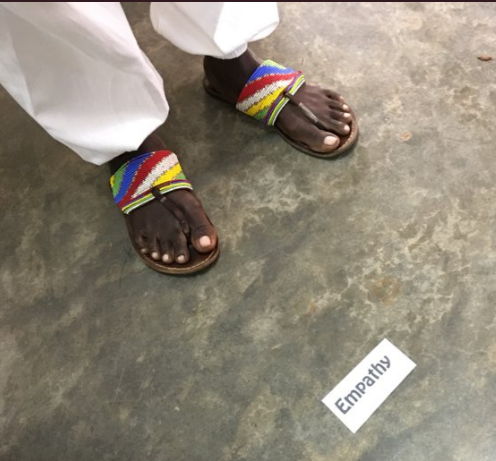

- A struggle of acceptance: Acceptance and understanding in work, families, and communities is an ongoing battle for people in both the UK & Uganda and something stigma contributes to greatly. Self acceptance seems a more complex issue to breakdown. “I am enough” and “This is me” were statements by members in UK & Uganda following the forum theatre participation. The teamwork, confidence building, shared experience, safe space, trust and acceptance from others was key to enabling self acceptance for participants and to realise that they were good enough.

- Judgement on wider capabilities:

In the performance created in the UK & Uganda, the academic / professional capabilities of people experiencing poor mental health were part of the story-line. Both stories also saw personal and romantic relationships breakdown, where partners were no longer seen as suitable.

In the performance created in the UK & Uganda, the academic / professional capabilities of people experiencing poor mental health were part of the story-line. Both stories also saw personal and romantic relationships breakdown, where partners were no longer seen as suitable. - Never letting go: Being allowed to recover is often a desire of people who have previously experienced acute mental health problems. I noticed no difference in the experiences of those people in the UK & Uganda; they described other’s inability to forget them at their worst moments, where they are referred back to even years later often causing feelings of shame and humiliation.

- A feeling of dis-empowerment: Not being listened to; lack of control; being spoken down to and having things done to them rather than with them is a common frustration.

We saw differences as equally striking:

- The concept of contagiousness: The idea that mental illness can be passed down, caught or damage future generations seemed much more widely believed in Uganda than in the UK. This also influenced the breakdown of relationships and the idea that people who had mental health challenges should be avoided as a partner. Many service users had been rejected and deserted.

- Causal and recovery beliefs: In the UK, people we know have different theories on the why and how of mental ill health, but these seem very different to beliefs widely held in Uganda. Traditional healers (which you may have heard people refer to as ‘witch-doctors’) are commonly used to remove spirits, and sometimes it is believed it mental ill health is the result of a previous life or behaviour, which adds to and changes the stigma, blame and isolation faced by people in Uganda. In the Ugandan play, a traditional healer diagnosed a young man (who the performance creators knew had bipolar) as experiencing a punishment by his step-mother’s jealousy. Traditional healers and rituals are a well accepted treatment. Talking therapies are much less widely available in Uganda. Medication is used widely by UK & Uganda, but interestingly in the UK where I feel the battle is to empower people to be less reliant on medication; in Uganda, the health sector is trying to encourage people to use, trust and rely on it much more for psychological problems.

The radical in the mundane

Strong and trusted relationships, where open and supportive conversations can take place, and problems can be shared are overwhelmingly what increases chances of long-term recovery, but stigma stifles. The ability to hold meaningful and non-judgemental conversations about mental health seems so simple, yet so difficult for either country to achieve. Both Forum Theatre performances saw the ‘spectactors’ step in to try out holding difficult conversations; negotiating ways to sensitively support people in need, and challenge others to rethink damaging stereotypes and stigma. The outcome on the characters was massive. Characters who were isolated, humiliated or feared, became able to be involved, valued and with purpose. Talking and treating others with empathy and respect, even at times where this might seem most difficult, seems an obvious, almost mundane answer to overcoming oppression, trauma and stigma. However, the Forum Theatre showed us these conversations could be life changing. One person’s words influenced not only those characters who were in times of inner turmoil, but reduced wider societal fear, increased understanding, and impacted on the way other people acted: This is when the mundane becomes radical.

Strong and trusted relationships, where open and supportive conversations can take place, and problems can be shared are overwhelmingly what increases chances of long-term recovery, but stigma stifles. The ability to hold meaningful and non-judgemental conversations about mental health seems so simple, yet so difficult for either country to achieve. Both Forum Theatre performances saw the ‘spectactors’ step in to try out holding difficult conversations; negotiating ways to sensitively support people in need, and challenge others to rethink damaging stereotypes and stigma. The outcome on the characters was massive. Characters who were isolated, humiliated or feared, became able to be involved, valued and with purpose. Talking and treating others with empathy and respect, even at times where this might seem most difficult, seems an obvious, almost mundane answer to overcoming oppression, trauma and stigma. However, the Forum Theatre showed us these conversations could be life changing. One person’s words influenced not only those characters who were in times of inner turmoil, but reduced wider societal fear, increased understanding, and impacted on the way other people acted: This is when the mundane becomes radical.

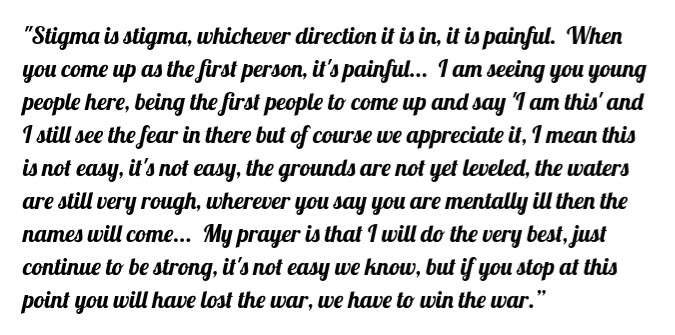

I would like to end this blog with the words of Uganda’s Health Minister Dr Hafsa Lukwata, who not only attended the Forum Theatre performance, but who was an active spectator, stepped onto the stage and took responsibility for the experiences of the vulnerable characters … characters who were in essence the same as those people who were acting them.

With thanks to Butabika Hospital, all the participants and Sharing Stories