Isolation to Radicalisation … What do we know now?

As someone following Odd Arts you are most probably already aware of our project ‘Isolation to Radicalisation’. Over the last 6 months we have documented our journey ‘posting’ quotes, pictures and daily reflections of the workshops online.

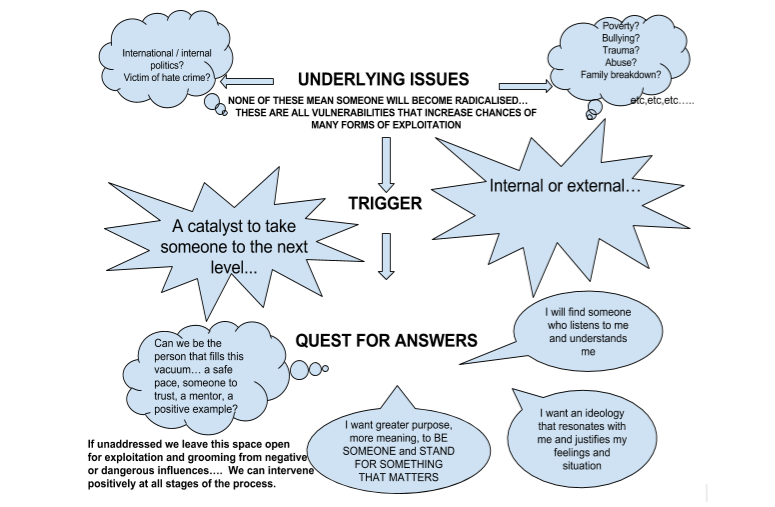

As noted in much more detail in our previous blog: ‘Manchester & Boston Radical Exchange’, the workshop includes a theatre performance highlighting authentic divisions around race, religion, and politics between 3 vulnerable college students. These issues are not dealt with, and the result… all the characters end up in grave risk of social isolation and radicalisation. Within the performance we highlight warning signs and triggers; and characters follow a common process seen in the route to radicalisation:

The performance looks at far right and DAESH inspired radicalisation. *We try to refer to ‘DAESH’ rather than ‘Islamic State’ to avoid it being confused as something reflecting Islamic practice.

The workshop uses an interactive theatre technique to bring in audience members to try and influence the outcomes and prevent the harm being done.

Now we do not profess to be specialists in terrorism and extremism, nor do we understand fully all the vast and complex international and internal politics that underpin much of the dangerous extremist behaviours and attitudes that exist. However, we are highly experienced in holding difficult conversations, we have worked for over 15 years with vulnerable, excluded and isolated groups, and we have a good understanding of safeguarding issues and vulnerabilities that make people more likely to take part in high risk behaviours. In the past 5 months we have worked with over 4500 young people, exploring issues around radicalisation, and wanted to share some of the key findings from doing so.

Our top ten tips for effective work around radicalisation:

1. Stop avoiding the difficult and awkward conversations:

We all know when it’s going on: Racism, Islamophobia; Anti-immigration attitudes, in other words ‘blaming the other’. Often we can find a way to avoid dealing with it: “I don’t know enough about it”, “They don’t mean it”, “People are entitled to their own opinion”, “I wouldn’t know what to say”… All valid concerns BUT who said you need to have answers. We don’t need answers, we don’t need arguments but we do need to to talk to one another. The more we listen, the more people are willing to open up and the more we understand about why other people (and ourselves) think the way we do. Are they / we angry, upset, fearful? Understanding the way each other feels means we can unpick attitudes, increase critical thinking and encourage new ways of seeing the world.

We were blown away by the young people’s willingness and openness to change. Notably more than many adult groups we work with, many of the young people would accept they had understood something wrong, critical of their own behaviour and honest about what they had learnt.

2. Preaching and shouting doesn’t work:

Often our gut instinct to tackle divisive, hateful or opposing attitudes to our own is to point our all the reason’s why we think THEY’RE WRONG. But ask yourself, have you ever witnessed this:

a: (to b) “You’re racist”

b: (in response) “oh yeah sorry I will stop being a racist now”

Although we want to ‘call people out’, often this approach is ineffective. Instead of blaming, shouting or pushing people away, can you find a different way to really challenge them? “Why do you think that?”, “Tell me more about what you mean there”, “I hear what you’re saying, you’re angry, I can see why, but I think…” This will once again open up a conversation and give more opportunities to challenge in a meaningful way. Which leads me on to my next point …

3. Validate people’s feelings:

People that are compelled to ‘do something’ be it ‘good’, or ‘bad’ are usually responding to strong feelings. Anger, hate, grief, injustice, jealousy, shame, sadness. When we try to gloss over negative feelings, it does not make them go away. A good example of this is when I say to my husband “That upset me” and his response is “well that’s stupid, you shouldn’t get upset about that”. Often I’m not looking for an answer, but simply to be acknowledged: “I can see that would upset you” *

If we want people to be less of a danger to themselves or others don’t deny their feelings, validate them. Acknowledge, without judgement what turmoil they may be going through and see if this makes them more open to talking, and eventually possibly more open to new ways of thinking.

*Note to self, send this to my husband 🙂

4. Be authentic:

Our first attempts at the performance were difficult. We felt the well know ‘fear of offending’ that often accompanies work around radicalisation. During one focus group someone pulled us up on one of the characters… “I don’t believe in him. This isn’t genuine. It isn’t enough for me to invest or care about him…” . Straight away we knew what was missing: An authentic voice. We had avoided some of the most upsetting and political voices out of fear of upsetting someone, but without these the performance was pointless because it didn’t hit that nerve, it wasn’t authentic. We went back to the drawing board and wrote into the script what deep down we knew already, and we voiced the elephant in the room. This was one of the best decisions we made. Young people who watch the performance time and time again said: “this is me”, “this is true”, “it’s real” – and it’s this authenticity that has enabled some of the most meaningful conversations. One young person disclosed: ‘I think I am being radicalised’*, something that was discussed in our workshop was real, relevant and relatable to them.

*All necessary safeguarding was put in place

Above photo, Odd Arts & actors trying to overcome initial challenges at rehearsal stage …

5. See radicalisation as a safeguarding issue:

Often people feel confident in addressing a young person at risk, with increased vulnerabilities. We aren’t frightened to discuss issues around drugs, sex, truancy, offending behaviour because we know we must respond with positive interventions and refer people to specialists or agencies who can prevent further harm. This is no different to a young person at risk of radicalisation. Approaching radicalisation as we do any other safeguarding concern makes it something many more people understand and have the confidence to deal with.

6. Teach skills:

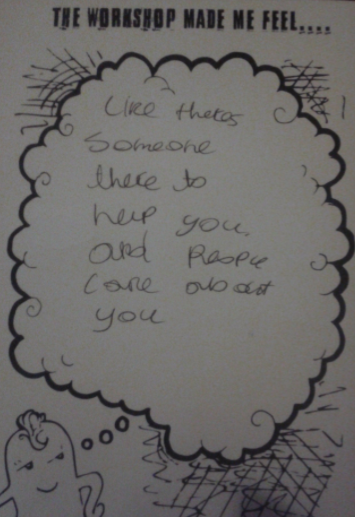

After reading over 4000 feedback forms you really do get a feel for what’s needed! An unexpected outcome from this work, is the value young people themselves gave to learning new conflict resolution, restorative and critical thinking skills. The interactive theatre performance asked them to think outside of the box, question why we act and feel like we do, be aware of the media influence, and find new (less aggressive) ways to challenge and combat hate and division.

Teachers and youth workers, as much as students, were enthusiastic to learn techniques and tactics for dealing with conflict and responding to challenging attitudes. Investment in these skills would hugely benefit community cohesion and resilience.

7. Avoid reaffirming stereotypes:

Muslim women are like this….

Immigrants are like this….

Middle class white people are like this…

Young black men are like this…

Teachers are like this…

See people as an individuals, with their own story, their own personality and their own identity. The more buy in to the idea of the ‘other’ the more likely we are to creative a divisive and more dangerous society.

8. Question yourself, question your concept of the ‘radical’:

Try to be aware of your own perceptions. Your take on the world is neither wrong or right. Are you Corbynite? Are you a Brexiteer? Are you a strict vegan? Are you very religious? Are you a sports fanatic? Could YOU be seen as extreme or radical?

Radicalisation is not a static state, it is a continuum people can drift up and down. At the lowest stage you have VERY STRONG OPINIONS, and right at the other end you have EXTREMIST TERRORISM. Do you sit on this continuum with any of your views? Is there a line where things go to far? Don’t be scared of any radicals… After all Manchester is known for the rebel and radical Emmeline Pankhurst, and where would we be without her!

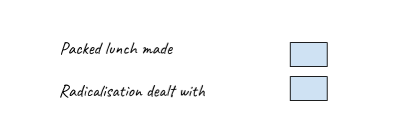

9. Know your job is never done:

This isn’t a one off conversation. Dealing with radicalisation needs to be a community wide approach. We need to hold these difficult conversations, question one another, and think critically long term. Dealing with the risk of radicalisation means dealing with isolated and vulnerable people. This does not mean daily discussions about extremist views, instead we should be normalising conversations about feelings, attitudes, justice, inequalities and how we understand the world. ‘Dealing with radicalisation’ is not something we can ever tick off as ‘done’, rather it is an approach to life and the way we interact with one another and society.

10. Deal with the issue before it’s an issue!:

The process of radicalisation (as drawn above) is complex and abstract. We will never know for sure if a someone was going to be exploited, groomed, or radicalised. Why wait? If you see signs of isolation, vulnerability, sadness, loneliness, fear, disengagement with society, or someone merely struggling to fit in, then deal with the issue you face. We can all take more responsibility and be more socially active by communicating more, and helping people feel safe, giving a greater sense of belonging, greater self worth and improved well-being. THIS is the first stage to tackling radicalisation.

With huge thanks to Manchester City Council who supported this programme of work, and the development of it.